Restoring the Public Trust: Why Parliamentary Oversight of State Assets Is Sound Governance

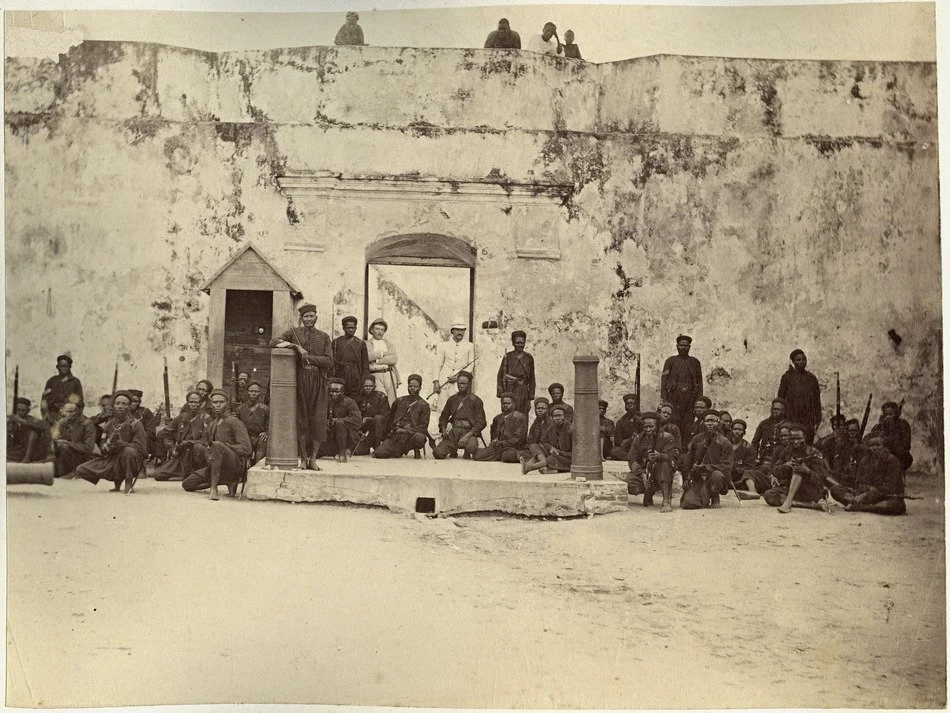

Keta

Date: 01.01.1880-31.12.1895

By V. L. K. Djokoto

The Strategic Logic Behind Mahama’s Land Reform Initiative

President John Dramani Mahama’s announcement that all future sales and leases of public property must receive parliamentary approval represents not merely administrative reform, but a fundamental recalibration of how democratic institutions relate to sovereign assets. The policy emerges from a recognition that the existing system has produced outcomes incompatible with the public interest.

The Problem: Market Failure in State Asset Disposal

The evidence President Mahama presented to Ghanaians in Zambia reveals a pattern that any serious analyst must acknowledge: systematic undervaluation of state property followed by spectacular private gains. When government land changes hands for GHS150,000 and subsequently sells for $2 million, we are not witnessing normal market dynamics. We are observing institutional failure.

This is not corruption in the conventional sense — it is something potentially more damaging: a structural arrangement that permits the transfer of public wealth to private hands at prices divorced from actual value. The mechanism may be legal, but the outcome is a form of involuntary subsidy from the state to well-positioned individuals.

The Institutional Deficiency

The current framework—where the Lands Commission processes transactions without legislative scrutiny — creates what might be termed an “accountability vacuum.” Technical bodies, however professionally staffed, operate within narrow mandates. They assess applications, verify documentation, process paperwork. What they cannot do, by design, is weigh competing public interests or assess whether a transaction serves the nation’s strategic objectives.

This is not a criticism of the Commission itself, but an observation about institutional limitations. No administrative body, insulated from democratic pressure, can effectively balance the complex considerations involved in disposing of irreplaceable public assets. Land, unlike financial instruments, cannot be recreated. Once alienated, it is gone.

The Case for Legislative Involvement

Mahama’s proposed legislation rests on a principle older than modern democracy: that the people’s representatives should control the people’s property. This is not innovation but restoration—a return to the basic logic that assets held in common require collective decision-making for their disposal.

Parliamentary approval introduces several corrective mechanisms:

First, publicity. Legislative debate forces transactions into the open. Private dealings with the Lands Commission can proceed quietly; parliamentary consideration cannot. Transparency itself disciplines behavior.

Second, deliberation. Parliament can ask questions administrative bodies do not: Is this sale necessary? Are the terms favourable? What alternatives exist? Could the land serve a higher public purpose? These are political judgments in the best sense — they require weighing values and priorities, not merely verifying compliance with procedures.

Third, accountability. Members of Parliament answer to constituencies. If they approve a questionable land sale, they face consequences at the ballot box. This creates incentives aligned with the public interest in ways that purely administrative processes cannot replicate.

Fourth, flexibility with standards. Parliament can establish clear criteria for what constitutes acceptable terms while retaining the ability to adapt to specific circumstances. This combines the predictability of rules with the responsiveness of judgment.

Addressing Predictable Objections

Critics will argue this adds bureaucracy, slows transactions, and politicizes technical matters. Each concern deserves consideration.

On efficiency: Yes, parliamentary approval takes time. But efficiency toward what end? If the current “efficient” system routinely transfers assets at a fraction of their value, it is efficiently serving the wrong objective. The question is not whether the new process is slower, but whether it produces better outcomes. A process that takes longer but prevents the loss of millions in public value is a net improvement.

On politicization: All disposition of public assets is inherently political — it involves choosing between competing interests and values. The issue is not whether politics enters the process, but whether it operates transparently or obscurely. Parliamentary debate politicizes openly; administrative discretion politicizes covertly. The former is preferable in a democracy.

On capacity: Parliament’s workload is legitimate concern. The solution lies in design —creating streamlined procedures for routine transactions while reserving full deliberation for significant disposals. Threshold values, standing committees, and clear timelines can make the system workable without sacrificing oversight.

The Broader Governance Context

This reform sits within a larger pattern in Mahama’s approach: the conviction that good governance requires strong institutions checking each other. Just as the judiciary must be independent but accountable, and the executive powerful but constrained, so too must control over public assets be distributed among multiple centers of authority.

The proposed legislation creates a system of dual keys: one held by the technical experts at the Lands Commission, one by the elected representatives in Parliament. Neither alone can complete a transaction. This redundancy is not waste — it is constitutional wisdom applied to asset management.

Advertisement

The International Dimension

Ghana’s approach, if implemented, would align with best practices in mature democracies where significant state asset disposals routinely require legislative approval. Britain’s privatizations in the 1980s went through Parliament. American federal land sales above certain thresholds need congressional authorization. The principle is well-established: major alienations of public property are legislative, not merely administrative, acts.

This matters for Ghana’s international standing. Transparent, legislatively-approved transactions are more credible to investors and development partners than opaque administrative processes. The reform strengthens, rather than weakens, Ghana’s investment climate by reducing the risk of future disputes over property rights.

Implementation Challenges

Success depends on execution. Parliament must develop capacity to assess land transactions—this may require technical support, independent valuation expertise, and clear procedural rules. The process must be transparent without being cumbersome, thorough without being interminable.

The committee reviewing existing transactions faces delicate work. Developed properties present particular challenges—retroactive repricing risks legal complications. But the principle Mahama articulated is sound: those who acquired undervalued assets should pay fair value. The law must find a way to implement this equitably.

Historical Vindication

Future observers will likely judge this reform not by the immediate controversy it generates, but by whether it prevented the continued hemorrhaging of public wealth. If, ten years hence, Ghana’s public lands remain substantially in public hands or have been disposed of at fair value for clear public purposes, the policy will be vindicated.

The alternative—continuation of the present system—leads to a predictable endpoint: gradual depletion of state property, concentration of land ownership, and widening inequality. These are not outcomes any responsible government can accept.

Conclusion: Defending the Public Interest

President Mahama’s proposal represents a straightforward application of democratic accountability to an area where it has been lacking. Public property belongs to the public. Decisions about its disposal should be made by public representatives, in public view, following public debate.

This is not radical reform. It is elementary governance. That it appears controversial reflects how far practice has drifted from principle. The proposed legislation simply closes a gap that should never have existed — the gap between the people’s ownership and the people’s control.

The measure deserves support not because it is politically convenient, but because it is institutionally sound. It aligns incentives with obligations, matches authority with accountability, and ensures that irreplaceable national assets are managed with the care they deserve.

In the final analysis, the case for parliamentary approval of land sales rests on a simple question: Who should decide what happens to property that belongs to all Ghanaians? The answer, in a democracy, can only be: the representatives of all Ghanaians.

This is what Mahama’s legislation achieves. It is what sound governance requires.