The Diplomacy of Empty Calabashes: Ghana’s Venezuelan Venture and the Art of Principled Irrelevance

By V. L. K. Djokoto

There is something peculiarly instructive, if not entirely edifying, in observing a government commit itself with such passionate intensity to a cause about which it knows rather less than it supposes and in which it has rather fewer stakes than its rhetoric would suggest.

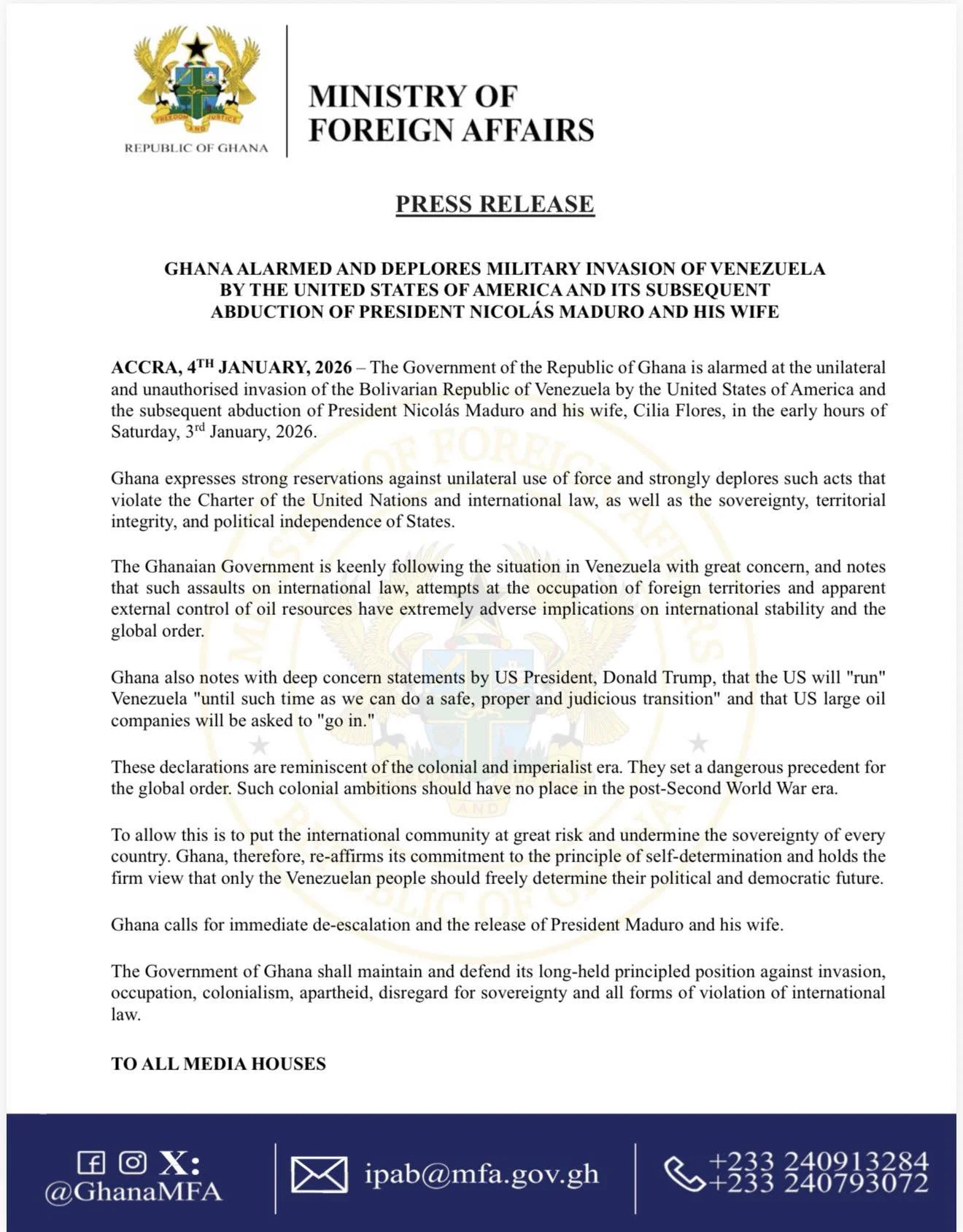

The Ghanaian Ministry of Foreign Affairs has produced a document that possesses all the moral certainty of an elder pronouncing judgment at a village durbar and rather less of the practical wisdom one might hope to find in serious statecraft — a condition, one might observe, that afflicts a great many pronouncements in our age, though rarely with such linguistic flourish.

The statement arrives bedecked in the full regalia of international law, sovereignty, and anti-imperial sentiment, rather like a chief attending a funeral in full Kente and palanquin when the occasion calls for quiet consultation in the compound. One cannot help but admire the theatrical quality of the performance even as one questions the necessity of the production. The language speaks of invasion and abduction with the kind of certainty that suggests either access to intelligence considerably superior to that available to most observers, or a commendable willingness to take strong positions on incomplete information — a quality that in other contexts we might call rashness, though in diplomacy we dress it up as principle.

What strikes the discerning observer most forcefully is not what the statement says, but what it reveals about the curious psychology of post-colonial diplomatic discourse, which seems unable to resist the temptation of casting every international dispute as a morality play in which the roles of villain and victim are assigned with remarkable haste and even more remarkable confidence. The invocation of the “colonial and imperialist era” functions here rather like libation poured to ancestors whose guidance one seeks but whose actual counsel one has no intention of following, transforming what might be a complex geopolitical situation involving competing claims, unclear facts, and genuine humanitarian concerns into a simple tale of aggression and resistance, oppressor and oppressed. It is a narrative framework of admirable simplicity and questionable accuracy — rather like those Ananse stories we tell children, in which cleverness always triumphs and wickedness invariably fails, and no one ever suffers from the inconvenience of moral ambiguity.

For those who profess allegiance to Nkrumah’s vision — and I confess a certain sympathy with the Osagyefo’s more sophisticated moments — this document presents a puzzle worthy of contemplation. Nkrumah, whatever his considerable faults and occasional grandiosity, understood that anti-imperialism divorced from strategic calculation was merely a form of self-indulgence, satisfying perhaps to the practitioner but rarely advancing the interests of the nation on whose behalf it was ostensibly performed. His non-alignment was a carefully calibrated dance, not a rigid dogma; a means of maximizing African agency in a world structured by others, not simply a pose struck for the benefit of domestic audiences and sympathetic observers. The current statement, by contrast, suggests a foreign policy conceived less in the chancelleries where interests are weighed than in the lecture halls where rhetoric is applauded — a distinction that matters rather more than the authors might suppose.

One is particularly intrigued by the section concerning oil companies and their prospective role in Venezuelan affairs, which the statement treats as self-evidently scandalous, as though the involvement of commercial interests in matters of resources were some novel innovation of the Trump administration rather than a pattern as old as the oil industry itself and considerably older than Venezuelan independence. Ghana, one might gently observe, is itself an oil-producing nation that has found it necessary to engage with precisely the sort of international energy companies that the statement affects to find so troubling. The country’s own economic development has required navigation of the complex relationship between resource sovereignty and the rather inconvenient fact that extracting oil from beneath the earth and selling it profitably on global markets requires capital, technology, and market access that multinational corporations happen to possess. To condemn in Venezuela what one negotiates in Accra is not hypocrisy exactly — that would be too harsh — but it does suggest a certain compartmentalization of thought that would benefit from more rigorous examination. It brings to mind the Akan proverb about the person who fetches water in a basket and complains of thirst — the problem lies not in the water’s absence but in the method of its collection.

The statement’s treatment of sovereignty is particularly revealing in its studied vagueness about what precisely sovereignty entails in an era when humanitarian catastrophes and state failures produce consequences that cheerfully ignore national boundaries. Venezuela’s crisis has already generated millions of refugees, destabilized neighboring countries, and created conditions of genuine human suffering — facts that the statement acknowledges not at all, preferring instead the comfortable abstractions of territorial integrity and political independence. This is sovereignty discourse as aesthetic performance rather than analytical framework, sovereignty invoked not as a principle requiring careful application to complex circumstances but as a talisman against the necessity of difficult thinking. It is rather like insisting that one’s compound walls remain inviolate even as fire spreads from the neighbor’s house —technically correct, perhaps, but spectacularly unhelpful in addressing the actual crisis at hand.

Advertisement

D. K. T. Djokoto & Co Advert

What the statement most conspicuously lacks is any indication that Ghana has considered its own interests in this matter with anything approaching the intensity it has devoted to expressing its moral sentiments. The question of what precisely Ghana gains from inserting itself into a hemispheric dispute in which it possesses neither influence nor direct stakes goes unaddressed, as though the making of statements were itself a sufficient end rather than a means to some larger purpose. This is foreign policy as gesture rather than strategy, diplomacy as theatrical performance rather than calculated positioning — and while there is undoubtedly an audience for such performances, both domestically and within certain international forums where anti-Western sentiment functions as a kind of diplomatic lingua franca, one wonders whether the applause is worth the price of admission. It recalls the situation of the person who spends his last cedi on a grand cloth for outdooring while his children go without school fees — the appearance is impressive, but the priorities are questionable.

The selective nature of Ghana’s outrage is particularly instructive for what it reveals about the actual drivers of this statement. The Ministry has been considerably more restrained in its responses to other violations of sovereignty — whether in the Sahel where foreign forces operate with varying degrees of invitation, in the Horn of Africa where borders are regularly contested, or indeed in situations where African states themselves have found it necessary to intervene across borders for reasons they deemed compelling. This pattern suggests that the principle being defended is not so much sovereignty in the abstract as sovereignty when its violation can be attributed to Western powers, and particularly American ones — a considerably more selective principle than the universalist rhetoric of the statement would suggest. It is rather like the situation of someone who objects strenuously to theft when committed by strangers but maintains a studied silence about pilfering within the family; the principle remains technically intact, but its application has become rather more situational than one might have hoped.

The invocation of the United Nations Charter and international law carries a certain ironic weight given that these instruments were themselves products of a post-war settlement that encoded existing power relationships even as it proclaimed universal principles. To appeal to international law while simultaneously condemning the post-Second World War order from which that law emerged is to engage in a form of logical gymnastics that would impress even the most flexible of contortionists. The statement wants simultaneously to invoke the authority of international institutions and to position Ghana as a critic of the order those institutions represent — a duality that might be philosophically interesting but is diplomatically incoherent. One cannot very well claim the mantle of international law while describing the system from which that law derives as fundamentally tainted by colonialism and imperialism; or rather, one can make such claims, but one should not be surprised when others note the contradiction. It is the diplomatic equivalent of swearing an oath by a god whose authority one simultaneously denies —effective perhaps as theatre, but rather less so as logic.

There is something almost touching in the statement’s apparent belief that diplomatic pronouncements function primarily as moral interventions rather than strategic calculations, that the purpose of foreign policy is to bear witness to one’s principles rather than to advance one’s interests. This is a peculiarly idealistic view of international relations, one that would have puzzled the elders who negotiated the intricate alliances of the Asante confederacy, who understood that survival required not merely the assertion of sovereignty but its careful cultivation through strategic marriages, tribute relationships, and the patient accumulation of diplomatic capital. The international system, for all the fine words inscribed in its charters and conventions, remains fundamentally a realm of interests rather than values, of power rather than principle — not because those who operate within it are uniquely cynical, but because states that consistently subordinate their interests to their principles tend not to remain viable for very long. To mistake diplomatic rhetoric for diplomatic reality is the error of the university student fresh from lectures; to base policy upon such mistakes is the privilege of states that can afford to learn expensive lessons.

One might have hoped for a more sophisticated approach, one that preserved Ghana’s genuine concerns about sovereignty and self-determination while avoiding the trap of premature judgment on contested facts. The country might have called for transparent international investigation, positioned itself as an honest broker rather than an advocate, offered its own experience with democratic transitions as a resource for eventual stabilization, and generally comported itself as a nation with regional leadership ambitions rather than as a state still performing the psychological rituals of post-colonial resentment. Such an approach would have required more subtlety and considerably less moral certainty, but it would have served Ghana’s interests rather than merely asserting them — a distinction that appears to have eluded the statement’s authors.

In the end, one is left with the melancholy conclusion that this document represents not the foreign policy of a confident, strategically minded state, but rather the diplomatic equivalent of performance at the independence anniversary parade — impressive in its pageantry, stirring in its rhetoric, but ultimately more concerned with appearance than effect. The statement will no doubt be well received in certain quarters, applauded by those who share its basic orientation toward American power and its reflexive sympathy for regimes that position themselves in opposition to Washington. Whether it will advance Ghana’s actual interests — in its relationship with the United States, in its standing within ECOWAS, in its reputation as a serious and pragmatic partner for development — seems at best uncertain and at worst unlikely.

The tragedy, if one may use so grand a word for so modest a misstep, is that Ghana possesses genuine diplomatic capital, earned through its relatively successful navigation of democratic transitions and its constructive role in regional affairs. To expend that capital on gestural interventions in distant disputes is to mistake the trappings of significance for significance itself, rather like the person who exhausts himself carrying an elaborately carved stool to market only to discover he has nothing left to sell once he arrives. Foreign policy, like farming, ought to be suited to one’s actual circumstances rather than one’s aspirational self-image — a lesson that the Ghanaian foreign ministry might profitably contemplate, though whether they shall do so remains, like so much else in this affair, a matter of conjecture rather than confidence. The calabash may be beautifully decorated, but if it holds no water, its beauty serves little purpose beyond admiration — and admiration, alas, secures neither harvests nor alliances.

The statement