Brown Gold, White Profit: The Cocoa Conspiracy

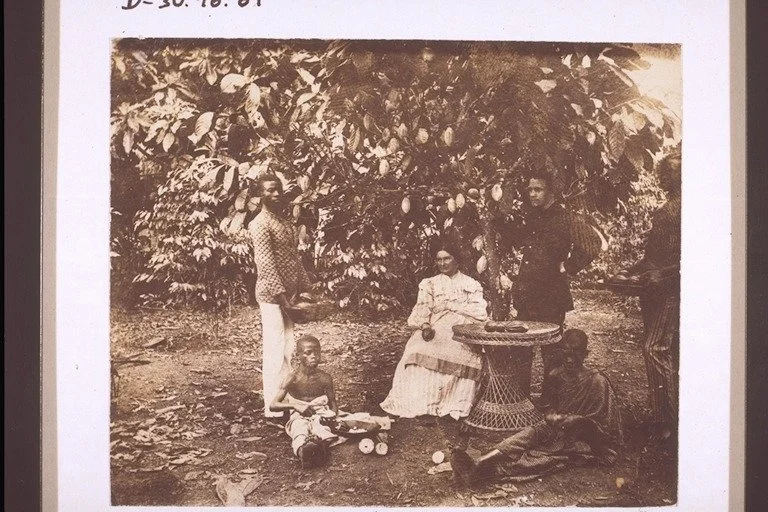

Cocoa harvest, Mrs. Ramseyer.

Title: "Kakao-Ernte. Frau Missionar Ramseyer. "

Creator: Ramseyer, Friedrich August Louis (Mr)

Date: 01.01.1888-09.04.1906

By V. L. K. Djokoto

The cocoa tree, that magnificent bearer of brown gold, stands as both monument and metaphor for our relationship with the global economic order. Its cultivation in Ghana tells a story not merely of agricultural enterprise, but of how power arranges itself in patterns that transcend the visible structures of governance, creating systems where wealth flows eternally toward established centres whilst the producers of that wealth remain perpetually on the periphery of prosperity.

The Rhythms of Extraction

One must contemplate the cocoa pod with a certain melancholy wisdom. Within its purple-tinged shell lies the seed of Ghana’s economic fate — a fate determined not in our own councils, but in the distant exchanges of London, New York, and Zürich, where men who have never felt tropical soil beneath their feet determine the value of our farmers’ labour. This is the essential paradox of our condition: we cultivate the earth, yet others harvest the profit.

The introduction of cocoa to the Gold Coast in the late nineteenth century has been celebrated as economic progress, the beginning of our integration into world markets. Yet we must ask with clearer eyes: integration on whose terms? The cocoa economy did not emerge from our own developmental vision, but was structured from its inception to serve the consumption patterns and industrial requirements of distant metropoles. Our farmers became expert cultivators, certainly — perhaps the finest in the world — yet this expertise bound them ever more tightly to a system where they possessed no leverage to shape outcomes.

Consider the delicate relationship between producer and price. A farmer in Ashanti tends his trees with ancestral care, watching the pods ripen under equatorial sun, harvesting at the moment of perfect maturation. Yet the price he receives bears no relationship to his skill, his effort, or even the quality of his beans. It is determined by mechanisms beyond his influence, in markets where speculation and strategic calculation override the simple logic of labour and reward. This arrangement — where those who create value cannot determine its price —represents not economic rationality but the continuation of colonial extraction by other means.

The Geometry of Dependence

The cocoa economy exhibits what we might term a structural asymmetry. Ghana produces; Europe processes. We export raw beans; they manufacture chocolate and capture the value-added premium. This division of labour appears natural, almost inevitable, yet it is neither. It is the result of deliberate choices, of investments made and withheld, of technologies transferred and denied, of markets opened and closed according to calculations of advantage.

The processing facilities, the shipping lines, the trading houses, the commodity exchanges —these remained, even after independence, largely in foreign hands or subject to foreign influence. We achieved political sovereignty whilst remaining enmeshed in economic relationships designed during colonial rule. The British departed from Christiansborg Castle, yet the fundamental architecture of economic subordination persisted, now maintained not by governors and gunboats but by debt obligations, currency dependencies, and the subtle pressures of international finance.

One observes a curious pattern: when world cocoa prices rise, the benefits accrue primarily to intermediaries, speculators, and processors in consuming nations. When prices fall, the losses are borne almost entirely by our farmers. This is not random misfortune but systematic design. The global cocoa trade functions as a mechanism for transferring wealth from periphery to centre, from the dark hands that cultivate to the pale hands that calculate.

The Psychology of Monoculture

There exists a deeper dimension to this dependency — a psychological architecture as constraining as any economic structure. When a nation’s prosperity becomes tethered to a single crop, when government revenues fluctuate with the whims of distant markets, when development plans must be revised annually according to harvest projections and price forecasts, a mentality of dependence takes root that proves extraordinarily difficult to uproot.

Our planners learned to think in terms of cocoa earnings, our budgets to rely on cocoa revenues, our future to depend on cocoa markets. This narrowing of economic imagination —this reduction of our vast potential to the cultivation of a single commodity — represents perhaps the most insidious legacy of colonial economic planning. We were trained to be efficient producers within a system designed for our subordination rather than architects of our own development.

The tragedy deepens when one considers the land itself. Acreage devoted to cocoa is acreage unavailable for food crops, for diversified agriculture, for the cultivation of economic sovereignty. As we expanded cocoa production to meet foreign demand, we became importers of rice, importers of wheat, importers of foods we could easily grow ourselves. The calculus seemed rational: specialize in what we do best, purchase what others produce more cheaply. Yet this logic ignores the strategic dimension — the vulnerability created when a nation cannot feed itself, when its food security depends on the goodwill of foreign suppliers and the stability of international markets.

The Illusion of Development Through Export

The conventional narrative celebrates Ghana’s cocoa success: tonnage increased, production techniques improved, quality standards met international requirements. By these metrics, we achieved remarkable progress. Yet we must interrogate the definition of progress itself. Is it progress when a nation becomes ever more efficient at producing raw materials for foreign industries whilst its own industrial base remains underdeveloped? Is it development when export earnings rise yet the farmers who produce that wealth live in villages without electricity, without clean water, without schools adequately equipped to educate their children?

The cocoa economy generated revenue, certainly, but revenue and development are not synonymous. Development requires the transformation of economic structures, the building of indigenous capacity, the creation of linkages between agriculture and industry, between rural production and urban manufacturing. The cocoa economy, structured as it was for export, created few such linkages. It existed as an enclave, connected more intimately to Liverpool and Hamburg than to our own nascent industries.

One observes the strategic calculations of the established powers with instructive clarity in this domain. They encouraged our cocoa production enthusiastically — for it served their industrial requirements and consumption preferences. Yet when we sought to establish processing facilities, to capture more of the value chain, to move beyond raw material export, we encountered suddenly a maze of obstacles: tariff structures that penalized processed goods, quality standards conveniently tailored to exclude our products, preferential trade arrangements that favoured established producers, and always the subtle message that we should remain focused on what we do best — which is to say, what served their interests most conveniently.

The Contradiction of Cooperative Exploitation

The cocoa marketing boards, established ostensibly to protect farmers from price volatility and merchant exploitation, illustrate the complexities of operating within inherited structures. In theory, these boards would stabilize prices, ensure quality standards, and capture surplus for national development. In practice, they often became instruments through which the state extracted resources from farmers — purchasing cocoa at below-market prices, accumulating reserves that financed urban development and administrative expansion whilst rural producers bore the burden of subsidizing the very state that claimed to represent their interests.

This is not to condemn the concept of marketing boards wholesale, but to recognize how even potentially progressive institutions, when operating within a global system structured for extraction, tend to reproduce exploitative relationships at a domestic level. The farmer who once sold to European merchants at unfavourable terms now sold to state boards at prices determined by bureaucrats in Accra who faced their own pressures from international creditors and foreign exchange requirements.

The pattern reveals itself with painful clarity: each link in the chain, from farmer to local buyer to marketing board to international trader to processor to retailer, seeks to maximize its own advantage. Yet the power to determine outcomes distributes itself unevenly along this chain. The farmer, most numerous and most essential, possesses least leverage. The final consumer in London or New York, utterly ignorant of cultivation processes, pays a price per pound that would astound the Ghanaian farmer — yet that price reflects primarily the value captured by intermediaries, processors, marketers, and retailers who never touched soil.

The Strategic Dimensions of Agricultural Dependence

From the perspective of global power arrangements, Ghana’s cocoa dependence serves multiple strategic purposes. It ensures a stable, affordable supply of a commodity essential to the confectionery industries and consumption patterns of wealthy nations. It creates leverage — for those who control markets can influence the behaviour of those who depend on access to those markets. It maintains a division of economic functions whereby some nations specialize in raw material production whilst others concentrate wealth, technology, and industrial capacity.

This arrangement did not emerge from the natural operation of market forces, though it is often presented as such. It resulted from specific historical processes: colonial investment patterns that developed export crops whilst neglecting food production; post-independence debt burdens that forced continued emphasis on export earnings; international financial institutions that promoted export-led growth whilst discouraging import substitution and industrial policy; trade agreements that opened our markets to foreign manufactures whilst restricting our access to theirs.

The genius of this system — if one can apply such a word to such exploitative arrangements —lies in its ability to present itself as mutually beneficial. Ghana gains foreign exchange; consuming nations gain cocoa. Yet this apparent reciprocity obscures fundamental asymmetries of power and value distribution. We sell what we must to earn foreign exchange for debt service and essential imports. They buy what they desire for discretionary consumption. This is not exchange between equals but transaction between the dependent and the dominant.

The Path to Agricultural Sovereignty

The cocoa experience teaches us that genuine development cannot be achieved through intensified participation in global systems designed for our subordination. We must cultivate cocoa, certainly — it is our heritage, our expertise, and an economic resource we cannot simply abandon. Yet we must transform our relationship to cocoa production, situating it within a broader strategy of economic sovereignty rather than allowing it to define our developmental horizons.

This requires several simultaneous transformations. First, diversification — not merely of crops but of economic activities, building the industrial capacity to process our own raw materials, to manufacture our own goods, to reduce dependence on imported inputs. Second, regional integration —creating markets among ourselves rather than depending entirely on the whims of distant consumers, building complementary economic structures that strengthen collective bargaining power. Third, strategic use of cocoa revenues — not for consumption of foreign luxuries or debt service to international creditors, but for investment in education, infrastructure, and industrial development that build long-term capacity.

Most fundamentally, we must reject the psychology of dependence — the learned helplessness that accepts our role as raw material providers, the internalized belief that we lack the capacity for industrial development, the conviction that our prosperity must always depend on the benevolence of foreign markets and investors. The cocoa tree, properly understood, should teach us not our limitations but our possibilities: what skill and dedication we bring to cocoa cultivation, we can bring to any endeavour. The question is not whether we possess the capacity for transformation, but whether we possess the will to undertake it.

Conclusion: From Bitter Harvest to Sweet Liberation

The cocoa pods ripen still in Ashanti forests, in Western Region plantations, in the Eastern hills where cultivation first took root. The farmers tend them with inherited knowledge and contemporary technique, producing beans of exceptional quality that command premium prices—premium prices they rarely see. This must change, not through moral persuasion or appeals to fairness, but through systematic restructuring of economic relationships.

We honour our farmers not by celebrating their endurance within exploitative systems but by transforming those systems. We demonstrate our sovereignty not by becoming more efficient exporters of raw materials but by building an economy that serves our needs and reflects our aspirations. The cocoa tree, that patient witness to our struggles, awaits not merely our cultivation but our liberation — the day when we determine not only how to grow it but what to make of it, what to charge for it, how to use the wealth it generates for our own development rather than the enrichment of distant strangers.

This is the revolutionary imperative: to transform bitterness into sweetness, dependence into sovereignty, extraction into development. The cocoa tree will flourish more beautifully when it grows in the soil of genuine freedom.